The triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem from Luke 19:28–44 signifies Jesus’ kingship in five explicitly messianic terms.

The following blog is an adaptation from Chad Harrington’s sermon preached on Sunday, November 13th, 2022 at Harpeth Christian Church in Franklin, Tennessee, which you can view directly below.

The “triumphal entry” in Luke 19:28–44 comes at a climactic point in Luke’s Gospel. Although Jesus had been to the temple in Jerusalem as a boy (Luke 2:41–52) and he had been tempted by Satan on the pinnacle of the temple (Luke 4:9–12), Luke does not record another trip of Jesus to Jerusalem in the entire Gospel of Luke—until Luke 19.

In this way, he builds the narrative toward Jerusalem for ten chapters, starting in Luke 9:51: “As the time approached for him to be taken up to heaven, Jesus resolutely set out for Jerusalem” (NIV, 1984). Three times between Luke 9 and 19, Luke says that Jesus was going to Jerusalem:

- Luke 9:53: “The people [in Samaria] did not welcome him, because he was heading for Jerusalem.”

- Luke 13:22: “Then Jesus went through the towns and villages, teaching as he made his way to Jerusalem.”

- Luke 17:11: “Now on his way to Jerusalem, Jesus traveled along the border between Samaria and Galilee.”

Readers can feel the anticipation building as they read Luke 19:11: “While they were listening to this, he went on to tell them a parable, because he was near Jerusalem and the people thought that the kingdom of God was going to appear at once.”

Finally Jesus arrives in Jerusalem in Luke 19:28:

After Jesus had said this, he went on ahead, going up to Jerusalem.

The King had entered the building, which felt to his disciples like hearing “Elvis has left the building,” but the opposite sentiment.

As the scene unfolds, Jesus:

- Instructs his disciples to take a colt for him to ride

- Mounts the colt and descends on it down the Mount of Olives toward Jerusalem

- Receives praise as King from his disciples

- Rejects the Pharisees’ attempt to dissuade him from receiving the praise

- Weeps over Jerusalem because the people don’t know “the things that make for peace”

For us reading this today, the colt, the descent down the Mount of Olives, and the praise probably don’t mean much. But to the crowd, they meant the arrival of God’s Messiah.

The Old Testament background to this passage reveals the rich meaning of this event in the story of the Gospels.

Note: this blog has only to do with Luke’s account of the triumphal entry, although it is recorded also in Matthew 21:1–17, Mark 11:1–11, and John 12:12–19.

What is the Old Testament background to the “triumphal entry” of Jesus?

The triumphal entry was definitively messianic. That is, Jesus was declaring himself God’s awaited king by how he entered the Holy City of God. We see this through five distinct nouns, I’ll call them, each of which point to Jesus’ messiahship.

Jesus’ triumphal entry also carries significance for us today (more on that at the end).

1. The Mount of Olives

Luke records that Jesus approached the Mount of Olives as he came near the towns of Bethphage and Bethany on his way to Jerusalem (Luke 19:29). We learn that he rides down the Mount of Olives on a colt.

How does the place of his descent signify his messiahship?

It points to the fulfillment of prophecy in Zechariah 14:1–11:

A day of the LORD is coming when… the city will be captured, the houses ransacked, and the women raped. Half of the city will go into exile, but the rest of the people will not be taken from the city. Then the LORD will go out and fight against those nations, as he fights in the day of battle. On that day his feet will stand on the Mount of Olives, east of Jerusalem, and the Mount of Olives will be split in two from east to west, forming a great valley, with half of the mountain moving north and half moving south. … On that day living water will flow out from Jerusalem…. The LORD will be king over the whole earth. On that day there will be one LORD, and his name the only name. … [The land] will be inhabited; never again will it be destroyed. Jerusalem will be secure.

This passage describes, first, the exile of the people of God into captivity (vv. 1–2). Then God goes to fight against the nations who took Israel captive (vv. 3–11).

Where does God’s restoration take place? God’s feet, so to speak (and in Jesus’ case quite literally), were planted on the Mount of Olives. This is the place from which Jesus descended.

The Mount of Olives was the pathway of God’s saving hand, and Jesus came down that mount as King.

2. The Disciples’ Obedience

Luke describes the obedience of the two disciples whom Jesus instructed to go into the city to get the colt. Now, we don’t know which city—Bethphage, Bethany, or Jerusalem—but they had to venture out and steal a colt, or so it might have seemed to onlookers.

He said, “If anyone asks you, ‘Why are you untying it?’ tell him, ‘The Lord needs it.’”

And the owners (“lords” in Greek) of the colt let them take their animal! Why? Because the Lord needs it.

They submitted their wills and their colt to Jesus, and their submissive obedience reveals their allegiance to Jesus as king. They recognized and affirmed Jesus’ kingship through their actions.

Even as they set him upon the colt they were saying with no words, “He’s our king.” This was not the first time disciples in the kingdom of Israel set their new king upon a colt. It happened in the coronation of Solomon, as well.

3. The Colt

On his deathbed, David had Solomon ride a mule on his way to his coronation to be king. King David said to his lead servants:

Take your lord’s servants with you and set Solomon my son on my own mule and take him down to Gihon. There have Zadok the priest and Nathan the prophet anoint him king over Israel. Blow the trumpet and shout, ‘Long live King Solomon!’ (1 Kings 1:33–34)

Solomon wasn’t just any king; he was the king who first received the fulfillment of God’s covenant to David:

When your days are over and you rest with your fathers, I will raise up your offspring to succeed you, who will come from your own body, and I will establish his kingdom. He is the one who will build a house for my Name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever. I will be his father, and he will be my son. When he does wrong, I will punish him with the rod of men, with floggings inflicted by men. But my love will never be taken away from him, as I took it away from Saul, whom I removed from before you. Your house and your kingdom will endure forever before me; your throne will be established forever. (2 Samuel 7:12–16)

Jesus’ riding on a colt literally put him in the typological pathway of Solomon, who was the first to receive the messianic promise of everlasting reign.

Jesus was the ultimate king, and he was the final king to receive the promise of an everlasting kingdom.

Plus the colt itself is a messianic signifier. How?

In Zechariah 9:9, we read about the saving king coming to God’s people on a donkey:

Rejoice greatly, O Daughter of Zion! // Shout, Daughter of Jerusalem! // See, your king comes to you, // righteous and having salvation, // gentle and riding on a donkey, // on a colt [LXX adds “new” / “young”], the foal of a donkey.

The precise meaning of “colt” in Greek here is imprecise, and its exact meaning inconsequential in light of first-century Jewish messianism and historiographical standards. The point that Jesus wants to ride a colt “which no one has ever ridden” comports with Zechariah 9:9 in the Greek version of the passage, which adds to the Hebrew “new” or “young” in front of “colt.”

By Jesus’ request to ride a young colt, he explicitly fulfilled Zechariah 9:9.

He was declaring as much—and more—as he rode that colt toward Jerusalem.

4. The Cloaks

The disciples put their cloaks on the donkey and then on the path in front of Jesus. Why? It seems arbitrary to those of us who don’t ride donkeys or have cloaks. But for the first-century Jewish disciple of Jesus who carried a cloak like we carry our coats during cold months, it fell in line with honoring Jesus as royalty. This is what Jehu’s men did for him, as soon as they found out he was anointed king.

Elisha secretly anointed Jehu as king, and in response, Jehu’s men “hurried and took their cloaks and spread them under him on the bare steps. Then they blew the trumpet and shouted, ‘Jehu is king!’” (2 Kings 9:13).

The disciples’ laying of cloaks on the path of Jesus signified their allegiance to Jesus as God’s chosen king.

If their actions don’t say it loud enough, then listen to their voices.

5. The Praise

It says they praised God in loud voices for the miracles Jesus had performed for them: “Blessed is the king who comes in the name of the Lord!” // “Peace in heaven and glory in the highest!” (Luke 19:37–38).

This was surely praise, but messianic praise?

Yes, indeed. The word “miracles” here is related to acts of power in Greek (Gk. dunamis). A word search of this term throughout Luke in the original language reveals that the people were praising Jesus for healing people’s physical ailments and casting out their demons.

These acts of power pointed toward Jesus’ kingship. He was God’s servant to save his people, heart and soul.

And he’s explicitly named in the praise as “king,” who comes “in the name of the Lord.” He’s the Prince of Peace who receives glory to God in the highest. This is high praise indeed; it’s messianic praise.

The Pharisees challenged Jesus to rebuke his disciples, which only confirms Jesus’ passive receiving of praise was indeed making a bold claim.

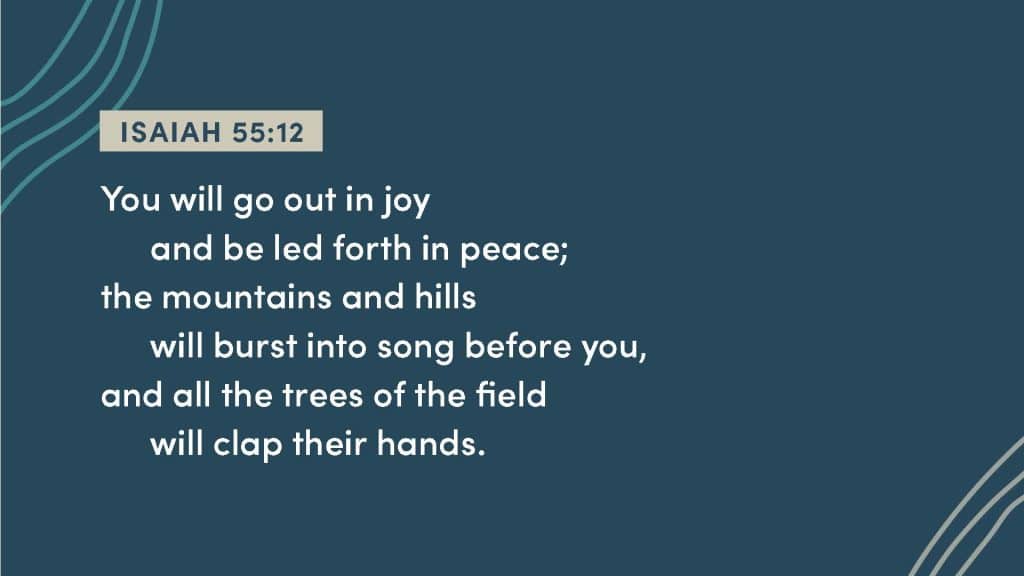

Jesus tells the challengers, “If they keep quiet, the stones will cry out.” This response confirms what Isaiah 55:22 said about God, represented here by Jesus:

Then we see Jesus’ heart as compassionate king come out, which reveals what kind of king Jesus is.

Jesus’ Tears for Jerusalem

Jesus’ tears pour out as he weeps over the people of the city. At the moment when the people might have expected a vengeful or militarily triumphant king, Jesus comes as a vulnerable victor. He’s a weeping king.

As he approached Jerusalem and saw the city, he wept over it and said, “If you, even you, had only known on this day what would bring you peace—but now it is hidden from your eyes.” (Luke 19:41–42)

What a beautiful scene as Jesus pours out his heart for the peace of God’s people.

In my sermon on this passage, I focus on what makes for peace in the ways of Jesus.

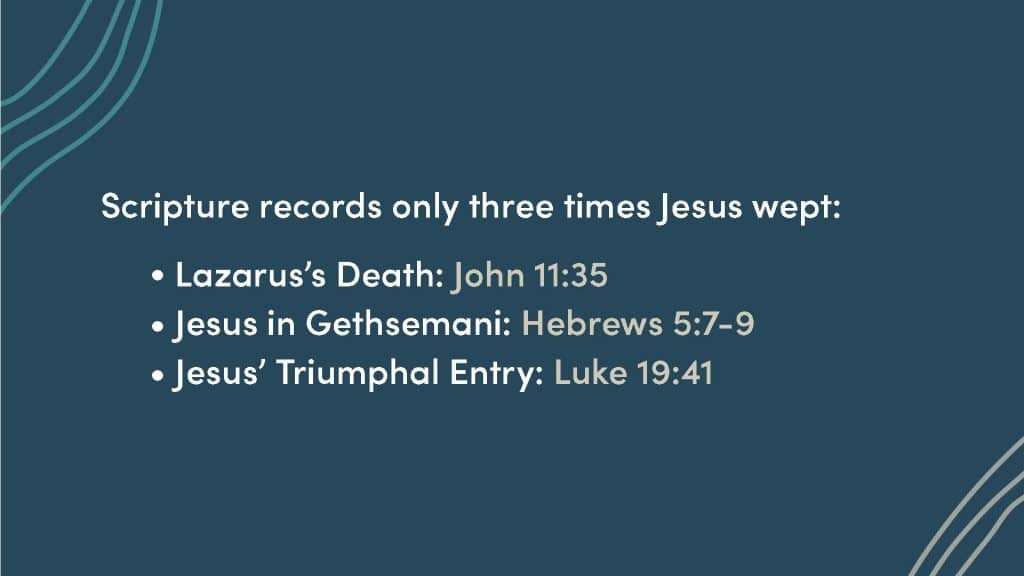

Jesus wept only three times in the Bible:

So this is a rare moment, where we see Jesus wearing his heart on his sleeve. And what do we see? Pure compassion for the people’s peace.

The Significance of the Triumphal Entry Today

When I lived in the Middle East in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, I often talked with the people about peace in their lands. I told them as often as I could, “The way to peace for Jews and Muslims is only through Jesus.”

This passage reveals that the pathway of peace is paved with cloaks of submission to King Jesus.

He offers himself as the means of our peace now as he did then. But our peace requires submission to him. What are “the things that make for peace”?

It’s obedience to the sovereignty of King Jesus. So here’s my encouragement to you:

Find your peace in King Jesus.

The world offers all sorts of paths toward peace, but Jesus offers the only lasting pathway of peace. His pathway is paved, in the end, by his blood.

His way toward peace was surrender to the will of God, and anytime we follow Jesus in humble submission, we take a step along the true pathway of peace.

Read more about Jesus as revolutionary from Chad Harrington in his book with Jim Putman, The Revolutionary Disciple.

Jim Putman’s and Chad Harrington's The Revolutionary Disciple

Walking Humbly with Jesus in Every Area of Life

A comprehensive discipleship strategy for your home, work, and church. You’ll benefit greatly from reading this book with your discipleship group or church staff.

— Robby Gallaty, pastor and author of Replicate

A long overdue call to us as leaders to humble ourselves before the Lord and the people we lead.

— Ed Litton, pastor and president of the Southern Baptist ConventionGet Product